camouflage

Camouflage and prey survival

Being spotted by a predator can mean certain death for many prey species, but surprisingly few studies have been able to test how real world prey survival depends on a prey’s level of camouflage from a predator’s point of view.

We are investigating camouflage in African ground-nesting birds such as nightjars and plovers. Using UV-sensitive cameras and computer models of predator vision we can test how well the different species match their backgrounds, and how this affects their survival.

We can also look for more subtle techniques the birds might be using to conceal their eggs against different background types, look at specialist versus generalist strategies, and compare background matching and edge disruption.

See my publications to see our latest findings.

Can you spot the nightjar?

There’s a Fiery-necked nightjar (Caprimulgus pectoralis) incubating her eggs in this image – can you find her? If you enjoy doing this, help our research and play our online games!

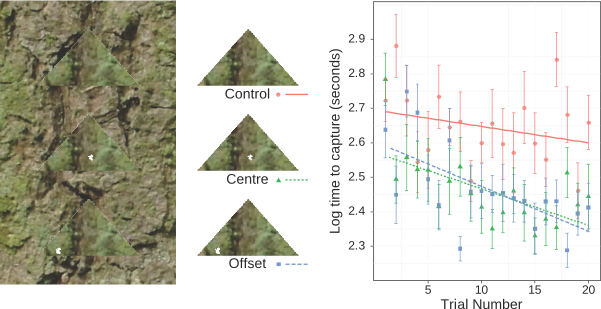

Distractive markings

The outline of a prey animal is thought to be an important cue for predators, so many camouflage types attempt to disrupt or hide this outline. Distractive markings are another technique that was first suggested by Abbott Thayer in 1909. These markings are thought to “direct the ‘attention’ or gaze of the receiver from traits that would give away the animal (such as the outline)” (Stevens & Merilaita 2011). So, for example; a bird’s gaze might be drawn directly to an interesting white blob on a tree without realising that the blob is surrounded by an otherwise background-matching moth.

This theory is still poorly understood, and empirical evidence in support of it is scarce. Working with Martin Stevens and other members of the Sensory Ecology group we ran a series of experiments to determine whether distractive markings improved the survival chances of artificial moths placed out in the woods for birds to find, and in a series of touchscreen computer experiments using humans as ‘predators’ (see my papers).

We didn’t find any evidence to suggest that distractive markings improve the survival of prey – these markings either made no difference, or made the prey easier to find. Moreover, we found that over successive trials our human predators learnt to find prey with distractive markings faster than plain background matching prey.

Be First to Comment